Floods, puddles and “strong” refusals

You’ve heard them. The doomsters. The gloomsters. Talking the system down. They’ll tell you planning’s slow. Well, to be fair, they may have a point about that bit: check out this Lichfields paper which shows that since 2014 the volume of applications have been dropping, and determination times have more than doubled. More. Than. Doubled. Gulp. To the point that - and this really is bananas - it’s quicker on average nowadays (for outline housing schemes anyhow) to plan by appeal to the Secretary of State. 🤯. Here’s one that goes straight into your bursting-at-the-seams “graphs that nail what’s wrong with the planning system” folder:

OK, so - granted - it can be slow (for one of the big reasons why, see Simon Ricketts here on multi-year s.106 negotiations). But they also say planning’s difficult. Well that’s where they’re wrong, friends. It’s a breeze. You want to make planning decisions under the NPPF? Don’t we all. EASY! Here it is in 4 cast-iron steps:

If you accord with an up-to-date development plan → grant. Simple. Right? [Er, not always… Ed. - here]

If there are no relevant development plan policies (rare) or the most important policies are out-of-date (less rare) → grant. Unless:

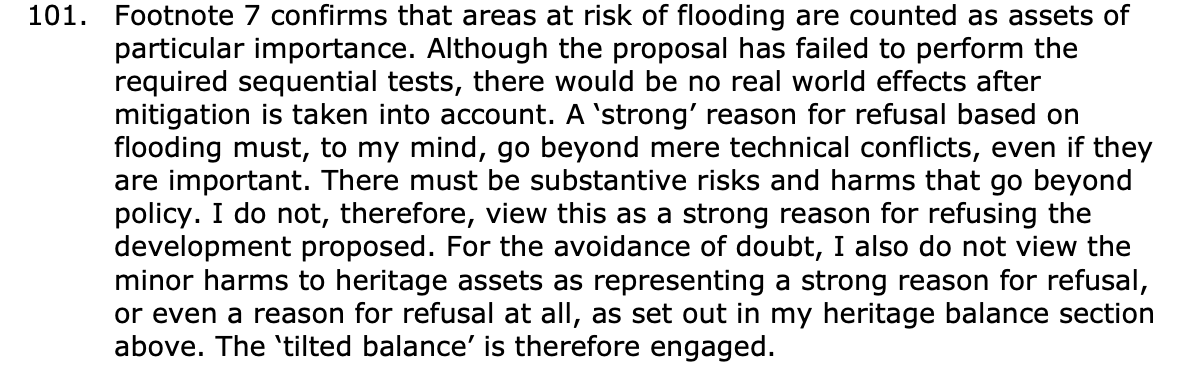

Either footnote 7 policies provide a “strong reason” to refuse. If they do → refuse.

Or harms significantly and demonstrably outweigh benefits. If they do → refuse.

That’s the gist, anyway.

Now. On that list, we’ve talked about (1), (2) and (4) before. Lots and lots and of times (the archive’s here if you’ve got some time to fill for deep cuts).

So. This is a post about (3) on the list. The “strong reason” bit. So very much turns on it. Now (i.e. in our “grey belt” world) more than ever. So. Here’s the question. Easy to ask, hard to answer:

When - dear reader - will a footnote 7 policy in the NPPF provide a “strong reason” to refuse planning permission?

Any ideas?

What, for starters, are “footnote 7” policies? They are these:

So far, so good.

Next: what is a “strong reason” to refuse permission? How do you know if you have one?

To warm up a little:

From 2018 - 2024, this policy language was slightly different. Permission was to be refused if the footnote 7 policies provided “a clear reason” for refusal. Clear. Clear?

Chapter and verse on “clear” reasons to refuse came in 2019 in the Monkhill judgment, where Mr Justice Holgate (as he was pre-promotion) set out a 15-point plan as to how this bit of policy works. 15 points. Among which are these important ones…

What counts is whether the application of a footnote 7 policy provides a “clear reason” for refusal. Just because a policy is engaged isn’t enough. A “clear reason” depends upon the outcome of applying the policy.

The application of some footnote 7 policies (e.g. Green Belt) at that stage required all relevant planning considerations to be weighed in the balance. The outcome of that assessment determines would determine whether planning should be granted or refused.

In other cases, the Footnote 7 policy may not require all relevant considerations to be taken into account, e.g. in the §215 heritage NPPF balance (more of which here) which requires "the less than substantial harm" to a heritage asset to be weighed against the "public benefits" of the proposal. Where the application of such a policy provides a clear reason for refusing planning permission, it is still necessary for the decision-maker to have regard to all other relevant considerations before determining the application or appeal.

There remains the situation where the footnote 7 policy does not provide a clear reason for refusal (e.g. heritage policies). In that case, even if you’re in conflict with them, you have to strike an overall planning balance applying, among other things, the "tilted balance" at (4) above.

Still with me?

Let’s take it a step further:

If there was a so-called “clear” reason to refuse permission under the old NPPF language, did that mean that permission necessarily had to be refused?

No.

A so-called “clear” reason to refuse may just be another thing to weigh in the balance, along with everything else. See, for one example, the Redrow and Mead cases I wrote about here. Flood risk. Sequential testing. More of this in a moment. But one of the judge’s points (it was that Mr Justice Holgate again!) was that a failure to pass the sequential test (leading to the engagement of, and conflict with, a Footnote 7 policy) is something to be weighed in the wider planning balance. It’s not - or not necessarily - a show-stopper (NB for completeness an appeal against his decision to the Court of Appeal failed - I wrote about it here).

Next: in 2024, the Government changed the language in this policy from “clear” to “strong”.

Why the change? The Government didn’t tell us. Not exactly. Although there was lots of talk at the time about “strengthening the presumption”, and… you know… one way of strengthening something is to throw a few “strongs” into it.

Another thing the new NPPF did do was define the “grey belt” - remember all of that? - to exclude land where footnote 7 policies, other than green belt, “would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development”.

So this idea of a “strong” reason for refusal has 2 big implications. It is a core part of the grey belt definition. And more widely, it determines whether schemes get to be determined under the so-called “tilted balance” at (4) above. So. This is a biggie.

What does the shift from “clear” to “strong” really mean? Well. What’s your take?

What do I think?

FWIW, I think that “clear” tells you how apparent something is, and “strong” tells you how important it is. All kinds of reasons could be “clear”. In the sense of e.g. “visible” or “evident”. But being clear doesn’t make them “strong”. In the sense of “firm” or “forceful”. For my money:

Shifting from “clear” reasons to “strong” reasons raises the bar. That was on purpose. “Strengthening the presumption” and all that. I.e. it’s now a tougher threshold to justify refusal under this policy than it was pre-2024.

“Strength”, in the end, requires a planning judgment. It has to. So there might be a footnote 7 policy engaged. It might be breached. It might weigh against development. So far, so clear. But clarity isn’t the test. Not anymore. Whether that clear breach adds up to a strong reason to refuse planning permission depends on the exercise of planning judgment.

Now, often that planning judgment will be pretty obvious. If, for instance, you’re talking about inappropriate development in the green belt, and you’ve decided that the relevant footnote 7 policy (§153 NPPF on “very special circumstances”) tells against a development, well… that’s basically that. You’ve weighed the benefits. You’ve weighed the harms. It’s a no. That’s a strong reason for refusal. Because that particular policy involves a test which - see Mr Justice Holgate above - balances all relevant planning considerations in the mix.

But the judgment won’t always be obvious like that. And a really good example of when it’s not obvious? Here it comes again… flood policy.

For a primer on what I’m talking about, have a read of this. If you want a deeper dive [Pun alert? Ed.], I did a presentation last year about all this with some brilliant colleagues from Landmark which can be watched here. TLDR: since 2022, thousands of pretty dry potential development sites all over the country have found that on account of what can sometimes amount to puddles (i.e. topographic depressions which show up on the EA’s pluvial flood risk maps), they are at risk of flooding. Technically. In theory. Even though in reality the design of any scheme would solve the risk (e.g. puddles can be flattened out). But due to e.g. those puddles (and to be clear - sometimes it can be an awful lot more than puddles - but oftentimes it literally is just puddles), developers sometimes have to do a sequential assessment of their site against tens or hundreds of other sites in the area, with the aim of showing that - somehow or other - they “pass” the “sequential test”. I.e. they’re the driest site in town.

When it comes to - in particular - so-called surface water or pluvial flood risk , the sequential test has become one of the most widespread barriers to development in England today. It’s right up there with s.106 delays on the list of reasons that application times have doubled (see that bananas chart above).

Why? Because it’s purist. It’s doctrinaire. It’s binary. It’s inflexible. It’s not interested in real world solutions, i.e. post-development. It’s not interested in whether a scheme can be safely delivered. Or a risk can be mitigated. Or balanced. Or solved. Or anything. As a policy mechanism, it only looks backwards. It’s just interested in the site as it is at the moment. Puddles and all. Mitigation-free. Devoid of solutions. And then it makes you go through the exercise - bizarre and illogical as it sometimes is - of trying to show the impossible, i.e. you’re the driest site in the county. Or the district. Or the town. Or wherever. What a strange state of affairs (i.e. why should you have to show that you’re not just acceptable, but also the driest site in the area to get a planning permission? What are we doing here? Does that mean that we have to develop sites 1 at a time, starting with the driest first and only then working our way wet-wards one permission at a time? Even in a world where there will be no actual risk of anything flooding with your development in place?).

And what if you don’t pass the sequential test? What then? What if there are some sites that are even drier than your site? Or what if… you just don’t do one at all?

Well, friend, you have then walked right into a conflict with NPPF flood risk policy. A clear conflict. And, no less, a clear conflict with a footnote 7 policy (i.e. flood risk).

So what does that mean? Curtains?

For the last couple of years, the planning inspectorate’s decisions have very much suggested that failing the sequential test, or not doing one when one’s technically required, was purchasing yourself a one-way ticket to a refusal.

But I want to show you 3 examples in the last few months which buck that trend. Which - if you’ll excuse me - turn the tide [Oh come on!, Ed.]. And by so doing, they get to the heart of what a “strong reason to refuse” really means both in the NPPF “presumption” policy above, and also in the definition of “grey belt”.

The 3 decisions?

The Secretary of State’s decision on a recovered appeal to grant permission for a new prison in the green belt in Lancashire: here.

A planning inspector’s decision to grant permission for 190 homes in flood zone 3a in Yatton, North Somerset: here.

A planning inspector’s decision - just the other day - to grant permission permission for 250 homes near the North Kentish coast in Faversham: here.

What do they show?

In the Lancashire decision:

A sequential test was needed because of surface water flood risk.

The Appellant (i.e. the Ministry of Justice) didn’t do one.

Nonetheless, because (i) it was admittedly difficult to find alternative sites for the prison, and (ii) surface water drainage scheme for the proposal has been designed to avoid any adverse off-site effects and so there would be no worsening of any existing flooding issues, only moderate weight was given to flood issues in the balance, and permission was granted.

In the Yatton decision (which - for completeness - is under a legal challenge, so I’ll update you if anything changes!):

A sequential test was needed because the site’s in flood zone 3a.

The Inspector decided the test was failed, and that there were 12 sites in the area which were sequentially preferable. He gave significant weight to that failure. But decided that it did not amount to a strong reason to refuse in circumstances where e.g. the evidence before the Inquiry showed a clear likelihood that meeting the housing needs of North Somerset over the plan period will require the allocation of a number of sites that are at risk of tidal flooding, and the proposed dwellings would not be at risk of flooding in the design flood event and would not increase flood risk elsewhere.

And so - permission granted applying the tilted balance (i.e. stage 4 above).

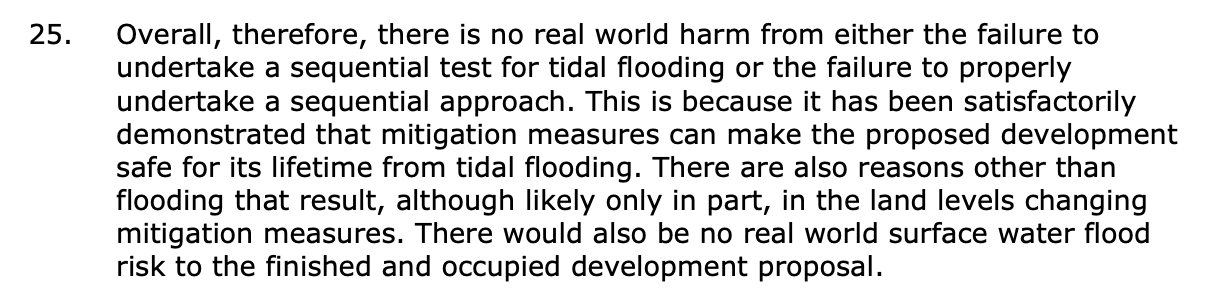

And then, the kicker IMHO, Faversham:

A sequential test was needed because the site’s near the coast, and because of surface water too.

The Appellant (Gladman Developments) did not do one. Only a few months back, this strategy hadn’t gone so well for them (albeit NB that refusal too is under challenge, so watch this space). And yet…

Appeal allowed on the basis of the tilted balance.

Why? Because, the Inspector said that the failure re the sequential test didn’t actually add up to any “real world” harm:

And, therefore, it wouldn’t amount to a “strong reason to refuse” because:

So. There you have it. Here’s the point - and goes a lot wider than flood policy:

For a conflict - even an important conflict - to be “strong” enough to kick you out of e.g. the definition of “grey belt” or the “tilted balance”, “there must be substantive risks and harms”. Not just theoretical ones. That’s what a “strong reason to refuse” is all about.

The Government’s been promising updates to flood risk policy for a long time now. Here’s hoping that updates come soon. And when they do, that they follow just a little bit of logic and good sense of the planning inspectors in Yatton and Faversham.

Stay cool, #planoraks. In this blistering sunshine. Keep your SPF-50 stocks up. Enjoy the tennis - if you’re that way inclined. And, whatever else you do, try your level best to #keeponplanning.